The Hauraki Gulf Protection Bill proposes 19 new marine protection areas (MPAs) with a more extensive ban on bottom trawling. But safeguarding our ‘beloved blue backyard’ for future generations may not be as straightforward as it initially appears.

By Lizzie Brandon

Established in 2000, the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (Tīkapa Moana, Te Moanaui-ō-Toi) is Aotearoa’s first marine park. It encompasses some 1.2 million hectares – that’s 20 times the size of Lake Taupō – and has been called the “seabird capital of the world”. Of the approximately 370 seabird species, 70 breed in, forage, or visit the Gulf. Five species only breed in this area, nowhere else in the world. It’s also home to common dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, orca, sharks, rays, and Bryde’s whales. Indeed, most of this endangered species live here. It’s an integral part of our lives for recreation, business, and delicious fresh kai.

The Hauraki Gulf truly is a taonga (treasured natural resource).

But it’s in trouble. The effects of overfishing, climate change, and other human interventions have taken their toll.

Just before Parliament rose, the Hauraki Gulf /Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill passed its first reading. The then Minister for Conservation, Willow-Jean Prime, said: “The Bill focuses on at-risk, high value and representative habitats that are home to an enormous variety of marine life.

“It is clear that we need sustained action to protect the Hauraki Gulf. The diverse ecosystems of Auckland’s blue backyard are under pressure, impacting the marine and coastal wildlife we know and love.

“Increasing marine protection for the Gulf will help to heal this damage and revitalise the unique marine space.”

The bill includes:

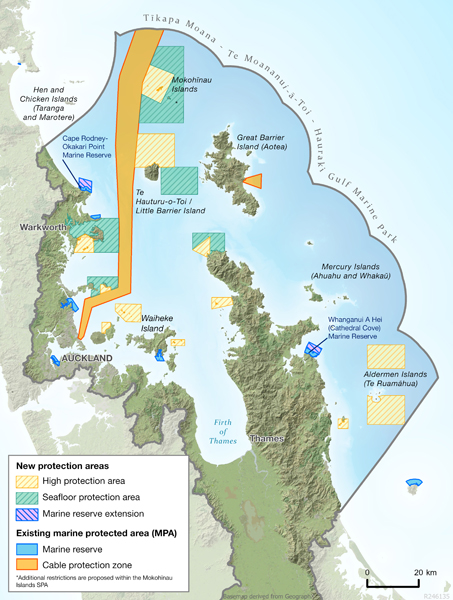

- Extending the country’s first marine reserve, Cape Rodney – Okakari Point Marine Reserve (Goat Island) and extending Whanganui A Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve, on the Coromandel Peninsula

- Twelve new high protection areas to protect and restore marine ecosystems, while allowing for customary practices of tangata whenua

- Five new seafloor protection areas to preserve sensitive seafloor habitats by prohibiting bottom-contact fishing methods and other activities which harm the seafloor

There are four options available for submission regarding trawl corridors. These would be the designated areas where bottom-trawling and Danish seining are permitted. The options propose banning these controversial commercial fishing methods in up to 89 per cent of the Gulf.

What is bottom trawling, and why is it so contentious?

Bottom trawling involves dropping large, weighted nets and dragging them along the sea floor. Danish seining (anchor seining) is similar, using a conical net. In 2021/22, more than 70 per cent of all fish caught commercially in New Zealand were done so with bottom trawl or mid-trawl, within one metre of the sea bed.

Seafood New Zealand contends that bottom trawling is “very limited in its extent and is highly-regulated [sic] and monitored by industry and the government to ensure sustainable practice”.

However, these methods can result in high levels of “bycatch” and cause environmental damage to the sea floor, including fragile ecosystems such as coral.

What’s been the response to the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Bill?

The bill has been widely welcomed in principle. That said, many organisations, including WWF-New Zealand and Forest & Bird, say it simply doesn’t go far enough.

Raewyn Peart, EDS (Environmental Defence Society) policy director, told ShoreLines that “overall, the Bill should be strongly supported” and that once in place, the MPAs “should make a significant contribution to restoring the healthy and mauri of the Gulf”.

“I am absolutely delighted … that we will finally see significantly increased marine protection in the Hauraki Gulf.

“It’s been a very long time coming, and has taken hard work by many people over many years, so it’s wonderful to see the initiative finally landing.

“The areas to be protected are all ecologically important in their own right, but collectively they will help restore the overall productivity of the Gulf, including enhancing fish production. In that way, everyone will benefit.”

She does, however, feel that the bill’s biodiversity objectives for each HPA (high protection area) need to be strengthened. “These are key to managing both customary practices and the consenting of activities within the protected areas. The biodiversity objectives need to be mandatory, and the process for developing them should be specified in the legislation, not left to regulations as is currently the case. There needs to be a transparent and scientifically robust process for their preparation.”

LegaSea, a non-profit dedicated to restoring the abundance, biodiversity, and health of New Zealand’s marine environment, supports the bill’s overall goals but with some provisos.

The organisation’s communications lead, Trish Rea, is a long-time fierce advocate for the wellbeing of New Zealand’s oceans. Her frustration and disappointment are palpable as she describes the demise of the Coromandel’s scallop beds. “They were dredged to death.”

She also explains how it is nigh on impossible to catch gurnard in the Gulf “unless you’re on a trawler in deep water” and that depleted fish stocks don’t just impact recreational fishers.

“We know that sea birds are starving. Adult birds are having to fly further away to catch food for their babies, as far as the South Island, and, by the time they return, their offspring have perished.”

LegaSea is pushing hard for an integrated approach regarding trawl zones. “There should be no dredging and no Danish seining in our backyard. However, evidence proves that banning these practices in one area merely displaces commercial fleets to another. Their priority is to fulfil their quotas. Commercial fisheries management have to be included in any decision-making. Otherwise, implementing a complete ban in the Hauraki Gulf without addressing the need to change catch limits could have dire repercussions for Bay of Plenty and Northland.

“If there’s an analogy, it’s like chucking your rubbish over the fence into your neighbour’s garden.”

Trish encourages voters to lobby their local MP. “Make it clear that this is a priority. There should be no more destructive fishing in the Hauraki Gulf.”

What more can we do to help protect and restore the Hauraki Gulf?

It’s important to remember that commercial fishing is not the only external factor impacting the health of the Hauraki Gulf.

In its State of the Gulf 2023 report, the Hauraki Gulf forum talks of the “coming storm”, saying that “mass mortalities of fish, shellfish and seabirds are likely to become increasingly common due to the impacts of climate change.” And that to increase the resilience of the Gulf by improving the health of its ecosystem, “we must act quickly and at scale”.

Now’s the time to have your say on the Hauraki Gulf /Tīkapa Marine Protection Bill

The health of the Hauraki Gulf affects us all – now and in the future.

The Bill is open for submissions until 11.59 pm on 1 November. Making a submission is an opportunity to share your opinions, observations, or recommendations.

To make a submission, go to:

parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/make-a-submission and search for Hauraki Gulf /Tīkapa Marine Protection Bill

Fisheries New Zealand is also accepting submissions on trawling in the Gulf. The deadline is 6 November: mpi.govt.nz/consultations/proposed-options-for-bottom-fishing-access-zones-in-the-hauraki-gulf

Suggested further reading:

beehive.govt.nz/release/next-steps-taken-protect-hauraki-gulf-t%C4%ABkapa-moana

doc.govt.nz/our-work/revitalising-the-gulf/new-marine-protections-in-the-hauraki-gulf

gulfjournal.org.nz/state-of-the-gulf