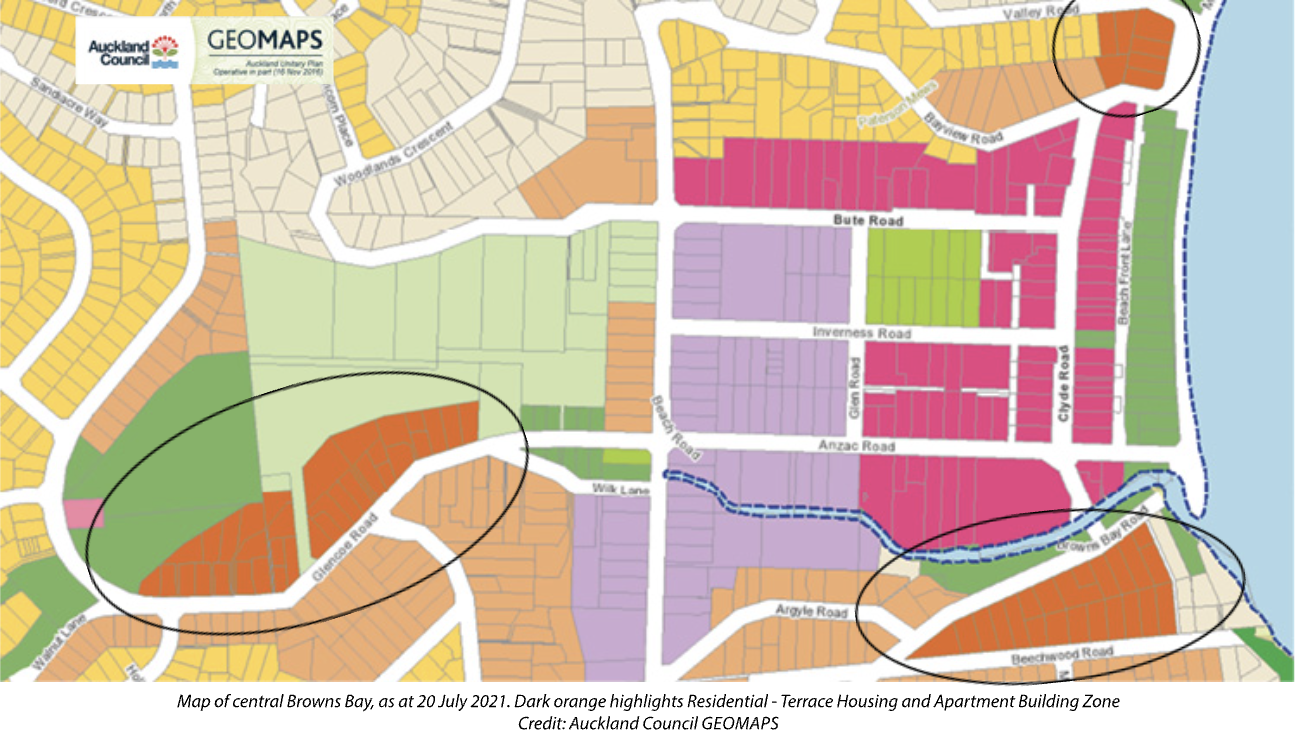

The Auckland Unitary Plan was introduced in 2016 as a “planning rule book” to bring consistency across Auckland. It replaced the Regional Policy Statement and 13 different district and regional plans. Essentially, the Auckland Unitary Plan is about the city’s future growth and sets out what you can build and where, by zone, for example, “mixed housing” or “single house”. It is the “terrace housing and apartment buildings” zoning that has precipitated the surge in new-build apartment complexes in the East Coast Bays.

Clare Ellis of Harcourts Cooper & Co Browns Bay confirms that apartments now account for 10 per cent of the branch’s listings. “There has been a rapid growth of apartment and town houses being built on the North Shore recently,” she explains. “Long Bay is a good example; we have sold more than $200 million in sales since February 2020, showing this area is sought after.”

In her team’s experience, the land purchasers are primarily developers. “The unitary plan has allowed new zones to open up on the North Shore. Developers are actively looking for ‘terrace housing and apartment buildings’ zones.”

Increased town house and apartment developments are certainly part of the solution to Auckland’s housing shortage, and Clare observes that first-time home buyers are looking at apartment living as an “affordable option” (at least by Auckland standards). Empty nesters, older singles and couples seeking to downsize are also looking to apartments as a convenient, lower maintenance option. Buyers of new-build apartments may also be looking to take advantage of the recent extension of the bright-line test period, which has an exclusion for newly built properties. This means that, if the apartment is new (acquired within one year of receiving the code of compliance certificate, under the Building Act 2004), the purchaser will only be subject to the bright-line test if they decide to sell within five years instead of the now-standard 10 years.

However, moving into an apartment complex may come with some restrictions, and potential buyers should always carefully check the body corporate’s rules and regulations. Clare recalls one instance when a lady bought an apartment and moved in with her small dog, only to find out that the rules didn’t allow dogs. The body corporate will also charge levies (fees or contributions) to owners to cover regular costs associated with common areas, such as gardening and cleaning. The fees for “an average” Auckland apartment block are currently about $5,000 per unit. The amount is set at the body corporate’s AGM and can change according to the OCR (official cash rate).

Despite their popularity, new-build apartments are not universally welcomed. Heritage groups have raised concerns, along with residents who have been confronted by the prospect of high-density housing where there were previously only a few single or two-storey properties. But, arguably, the introduction of shopping malls has already had the most significant impact on village life – taking consumers out of town centres. “Once The Victor, The Kauri, and The Anzac Lofts are all occupied, there will be about 300 more people living right here in the centre of Browns Bay,” says Clare. “This will create more confidence for potential and existing businesses, with increased foot traffic.”

Despite their popularity, new-build apartments are not universally welcomed. Heritage groups have raised concerns, along with residents who have been confronted by the prospect of high-density housing where there were previously only a few single or two-storey properties. But, arguably, the introduction of shopping malls has already had the most significant impact on village life – taking consumers out of town centres. “Once The Victor, The Kauri, and The Anzac Lofts are all occupied, there will be about 300 more people living right here in the centre of Browns Bay,” says Clare. “This will create more confidence for potential and existing businesses, with increased foot traffic.”

Browns Bay’s town centre manager Kim Murdoch agrees. “Higher density apartment living in Browns Bay centre brings more people to live in the immediate proximity of our shops, businesses and hospitality. While many people seem concerned about the changing face of our seaside town, this will have positive outcomes for our local economy. Also, with the drastic evolution of consumer spending habits due to the Covid-19 pandemic, more people want to support local in favour of driving to the mall. Evidence even suggests that online shopping is being done supporting local. Brand new retail tenancies, such as those on the ground floor of The Victor luxury apartments, set welcome new standards for retail tenancies.”

Retirement village living

As well as the burgeoning apartment complexes, ShoreLines‘ catchment area also contains almost 10 per cent of Auckland’s 94 retirement villages.

| 422 | Retirement villages in New Zealand |

| 36,300 | Retirement village units in New Zealand |

| 47,249 | Estimated total number of retirement village residents in New Zealand |

| 67,880 | Expected 75+ population growth in Auckland between 2020/33 |

| 12,100 | Expected growth in retirement village residents in Auckland between 2020/33 |

| 81,000 | Expected total number of retirement village residents in New Zealand by 2033 |

Research from JLL NZ’s whitepaper New Zealand Retirement Villages and Aged Care | June 2021

Wanting to gain a better understanding of this lifestyle choice, ShoreLines approached several local retirement villages. Ian Dunthorne, general manager of Bupa Hugh Green Retirement Village & Care Home in Rosedale, and Sharon Rabone, sales manager at Aria Bay in Browns Bay, were kind enough to respond with their and their residents’ thoughts.

What do your residents tell you were their reasons for moving into your retirement village?

Security while still maintaining independence ranks highly, as does a handy location close to local amenities. “Continuum of care” is important – having rest home, hospital and (in the case of Aria Bay) specialist dementia care on site offers peace of mind. Wanting to relax and lose the stress of property maintenance is attractive too.

What makes your retirement village different from others in the area?

Residents appreciate the smaller size of both these properties. Hugh Green’s residents tell Ian they like “a reputable company behind us” and “feeling part of a family”. Aria Bay’s “Attitude of Living Well” household care model is popular.

In your experience, what are the common reasons why people decide not to move to a retirement village? What are the barriers?

There are two key concerns: fear of downsizing (that this is going to be the last move) and a feeling that “I’m not ready for retirement living” (even though the person is retired!)

What do your residents tell you has surprised them about retirement village living? What were they not expecting, or what are the benefits they hadn’t considered?

Again, Ian and Sharon agree on a key point: companionship! Ian hears from residents “how easy it was to settle in,” and Sharon understands that “the community spirit and the friends they make have completely surpassed their expectations”. Other unexpected benefits from Hugh Green’s residents include lower costs than fixed fees, still being able to do the garden, activities and outings, and feeling that you can be “as social or as private as you like”.

Retirement village living: a legal perspective

“I’m a fan of retirement villages,” says Rowena Lewis, director of Lewis Mortimer Law in Browns Bay. “I have clients moving into them all the time; some even relocate to Papamoa and Tauranga.” She says that clients have many reasons for purchasing a villa or apartment in a retirement village – the sense of security, freedom from house maintenance, village community involvement, freeing up some cash, and that the village may offer rest home and hospital services if required in the future. Also, there can be no pressure to purchase as the law requires legal advice with at least a three-week cooling off period.

Rowena stresses that it is most important to be properly advised. This includes ensuring that EPAs (enduring powers of attorney) are in place and carefully checking the retirement village’s contract, as these vary from property to property, and are periodically updated. “What you’re signing today may not be the same as what your friend signed a few years ago.”

If she does hear complaints, she says that these “aren’t really that loud” and are mainly from the client’s family. They tend to arise after a unit has been vacated and concern the percentage that the village retains (20-30 per cent of the purchase price), lack of capital gain, how long the weekly fee will continue, cost or necessity of refurbishment, or the length of time it takes to be paid out.

In one financial respect, however, Rowena feels that apartments in retirement villages may offer a potential advantage over “standard” multi-unit complexes. This relates to body corporate fees. If, for example, a complex required significant repairs or upgrades, the body corporate would invoice every owner for a percentage of the total bill – which could easily be for thousands of dollars and an unwelcome surprise. On the other hand, retirement villages usually charge a lifetime weekly fee, which could be simpler to budget for.