Managed retreat is not a new concept, but since January’s floods and the devastation of Cyclone Gabrielle, it’s a term that’s been heard much more frequently. Indeed, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins has said there will have to be some “tough calls about managed retreat” in the wake of these recent events.

In the first of a two-part special feature, ShoreLines’ editor Lizzie Brandon investigates what this means and how it could impact our everyday lives.

Managed retreat is one type of climate adaptation response. It involves identifying geographical areas considered at exceptionally high risk due to weather events, and relocating homes, businesses, and sites of cultural significance in a planned and progressive manner.

This serious issue is far from unique to Aotearoa New Zealand. A 2017 report[1] looked at “27 past and ongoing efforts to implement managed retreat” in 22 countries around the world, reporting that “approximately 1.3 million people” had already been relocated through the process.

[1] Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk, Miyuki Hino, Christopher B Field and Katharine J Mach

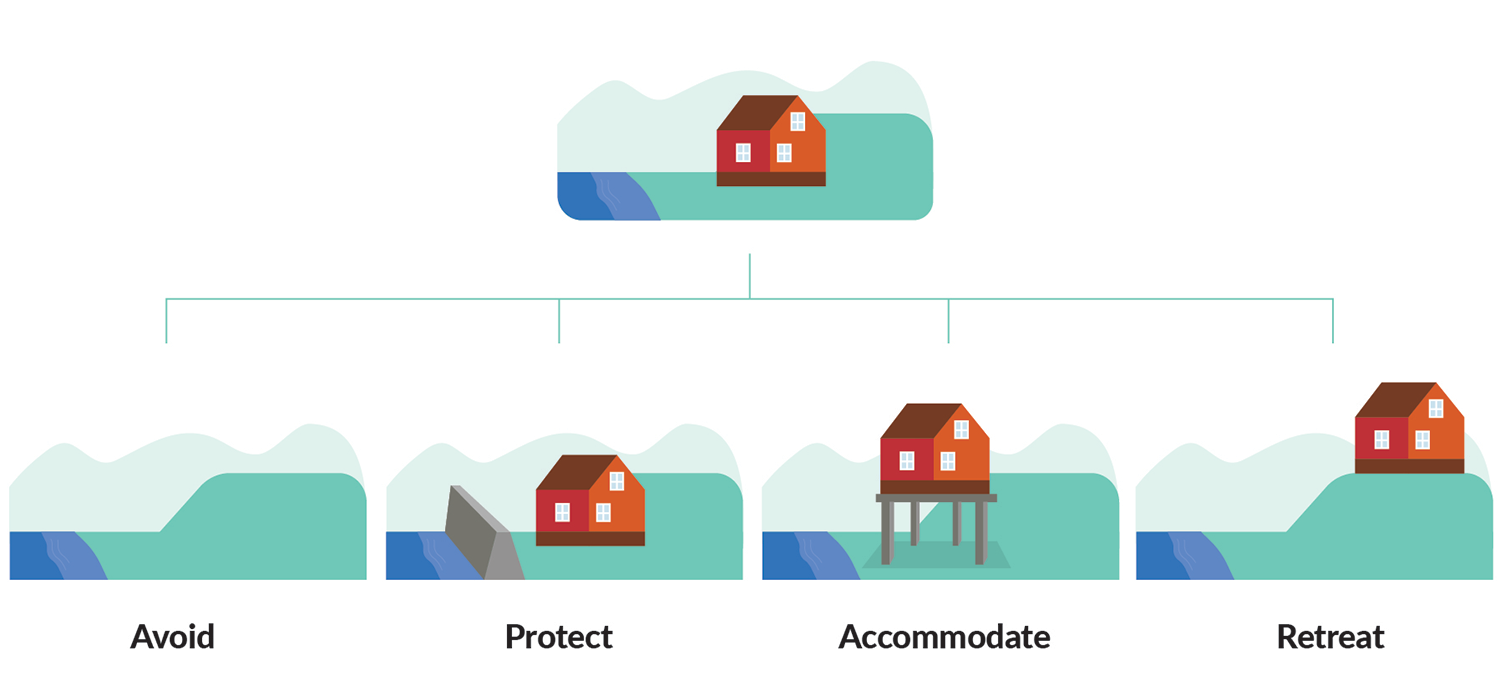

The Ministry for the Environment Manatū Mō Te Taiao states: “We can adapt to climate impacts by protecting our assets (e.g., sea walls), accommodating for the change (e.g., raising properties or rebuilding more resiliently), or managed retreat (moving away from the risk).

According to figures released by the Ministry for Environment last year, approximately 750,000 Kiwis and 500,000 buildings worth more than $145 billion are near rivers and in coastal areas already exposed to extreme flooding. In April /May 2022, the ministry consulted publicly on managed retreat alongside the draft national adaptation plan to try and consider what an effective managed retreat process would look like. The consultation underlined that managed retreat is just one option for vulnerable areas, stating: “It is usually not considered in isolation from other options, especially when planning for future rather than current impacts of climate change. In some cases, retreat may be a last resort, and in all cases, the costs and benefits will need to be carefully weighed.”

Feedback from this consultation will ultimately form part of the Climate Change Adaptation Act (the CCA) – but that’s not the only legislation involved.

As Te Kāhui Ture o Aotearoa the New Zealand Law Society explains, managed retreat: “requires some support for resettlement of the home owners and key infrastructure (the CCA) but also the identification of a new area to settle together with the implementation of key infrastructure like roads, power, water and sewerage (the NBA [National Adaptation Plan] and SPA [Strategic Planning Act]).”

If you’re starting to think that this all sounds extraordinarily complex, you’re not wrong!

And we haven’t even begun to discuss how this is going to be funded. There are the costs associated with the research to identify vulnerable areas, plus the costs of relocation and providing integration and adequate infrastructure elsewhere.

The Law Society goes on to infer that financial responsibility may primarily lie with local authorities but states: “It is essential that an additional funding stream is provided from a central source to ensure local authorities are in a position to implement managed retreat rather than leaving authorities to raise funds from ratepayers or user pay services that are already under strain.”

There’s another very thorny aspect to all this.

In the Deep South Challenge research report[1], Insurance Retreat, Belinda Storey of Climate Sigma attempted to look at how the insurance sector would respond to the “ever-increasing impacts of climate change”. Her findings suggest that, within the next 25 years, at least 10,000 homes in NZ’s four biggest cities will be deemed uninsurable.

These are properties within 1km of the coast and in one-in-100-year flood zones.

[1] Climate change and the withdrawal of insurance deepsouthchallenge.co.nz/research-project/climate-change-and-the-withdrawal-of-insurance

Ms Storey commented: “Once insurance is unavailable, property buyers will find it difficult to borrow money to purchase a property, and existing owners may need to make expensive modifications to their homes to prevent flood waters reaching inside.

“Insurers may be willing to continue to provide insurance to high-risk areas if active differentiation between these areas and lower-risk area is widely accepted. This differentiation could include policy exclusions or very high premium prices and excesses.”

Frustratingly, at this stage, there are many more questions than answers, but what’s clear is that these issues will only gain significance.

In our June /July issue, Lizzie will look at the positive steps that can be taken. She’ll be chatting to Massey University’s professor of construction management Suzanne Wilkinson, about ‘building back better’. How should we build sustainability, climate adaptation, and mitigation into construction projects? And what might homes of the near future look like?

This year’s weather events were stressful, shocking, and extremely difficult for so many in the Bays. But they also brought out the best in our community. Social media was full of shout-outs to those good souls who got together to support their neighbours. Here are just three examples.

Kalin and her family live in Torbay, off Deep Creek Road. Kalin runs her small business, Bath Buddies, from home too.

The creek at the bottom of their property is non-tidal and “normally a trickle”. It took only minutes between the creek bursting its banks to it filling their home. At its peak, there was only a 30cm gap below two-metre-high ceilings.

“Our friends arrived in droves; they’ve been phenomenal.”

The family would like to sincerely thank Erica Stanford MP, Agak Agak Food, New World Long Bay, and Torbay Fruit Shop for their kindness and support during a very challenging time.

The Murrays Bay beach clean-up was a collaboration between Josie Adriaansen (past president of the residents’ association), Scott Leith (Murray Bay Sailing Club), Julia Parfitt – and more than 200 locals, who came armed with buckets, spades, and wheelbarrows.

Auckland Council (AC) provided two skips, which were also emptied and returned to site to be refilled. AC also checked the boat ramp and made repairs to ensure it was safe and fit for purpose.

Josie gratefully acknowledges Sage and Brew Café for providing a wonderful morning tea, supplemented by locals’ delicious baking.

In a fantastic show of community spirit, local caterer Cynthia Sim of Agak Agak Food donated 250 Malaysian curries to families affected by the floods.

[1] Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk, Miyuki Hino, Christopher B Field and Katharine J Mach

[2] Climate change and the withdrawal of insurance deepsouthchallenge.co.nz/research-project/climate-change-and-the-withdrawal-of-insurance